DNA provides information about physical characteristics and perhaps even propensities. But literature, I argue, also offers insights into a family’s legacy. Take the story of my Saul side-- it is familiar, almost stereotypical. Eastern European immigrants come to the US in the 1880’s and within a generation become Americanized. In the South, the Midwest and eventually Hartford, CT. they learn new ways of communicating and making a living. Males join the military, females go to college. The Sauls all have surprisingly good voices and like to sing; they are also known for their excellent memories. They know how to smile and hug one another. They suffer, on occasion, from depression and self-doubt.

The story of the Rappoports is different--both extraordinary and personally repulsive. One of my readers asked about what happened to the Minerva, the hand-built Belgian car mentioned in my last post. She might also have asked about what happened to the the many paintings, the tapestries, the jewelry (including a blue diamond), the museum-quality furniture, the silver and the real estate. In short, this was a family that collected “stuff,” objects, things—that which could be seen and touched. The Rappoports trusted the value of stuff more than money--if you had good taste and bought enough stuff at bargain prices, its value would surely increase. And meanwhile, it could be displayed. No IKEA purchases for this gang!

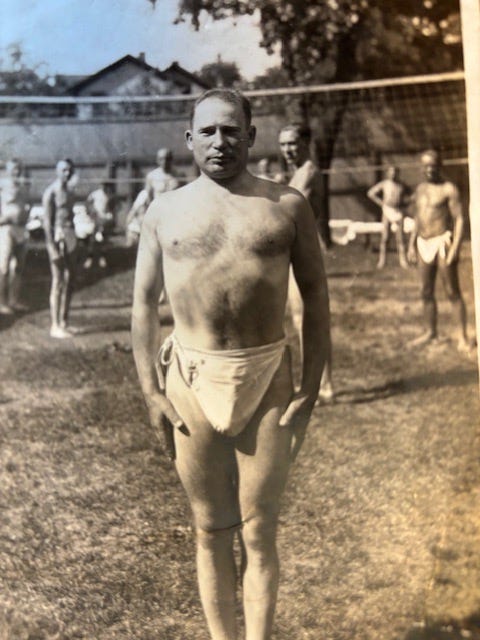

Like Jack, of Beanstalk fame, Philip Rappaport’s origins were indeed modest. A native of Lodz, Poland, he arrived in the US in 1905 , one month before his 18th birthday. As a religious, Kosher Jew he ate can after can of sardines, and prayed morning and night while negotiating the indignities of steerage class. Phil’s mother had died in childbirth, but her brother, who lived in the Paterson, NJ, aka Silk City, met his young nephew at Ellis Island. The uncle found Phil work as a weaver and Phil lived with their family until his marriage in 1916.

Minnie, the wife to be, was a native of Belarussia, who came to the US in 1902 when she was 7. Her father was a housepainter who had arrived earlier with the help of his father-in-law. The Shelkowitz family found an apartment in Brooklyn, where Jacob, his wife Chaya Esther and their six children lived until Minnie met Phil. I have no idea how, given her roots, Minnie became so conscious and enamored of status, but enamored she was. She learned to speak a nearly perfect “King’s English,” used a sophisticated vocabulary, and developed excellent penmanship, spelling and grammar. When the census taker arrived at the family’s door in 1910, Minnie answered that her family spoke German rather than Yiddish. And that she was born in the USA. Minnie graduated top of her class from secretarial school and got a good job in the garment district. There, in about 1914, a boss or fellow employee fixed her up on a blind date with young Philip Rappoport, who by then, (shockingly) co-owned a silk mill.

Phil apparently showed up in Brooklyn for his big date in a new Ford, driven by a mill employee dressed as a chauffeur. An optimist and talented entrepreneur, my guess is that he and Minnie both reckoned that her acquired “classiness” would compensate for his embarrassing, accented English and religiosity. Like Jack of Beanstalk fame, the couple had no sense of “enough” and found pleasure, again and again, in having more.

What made them think/believe that they, though not so different than any of the thousands of immigrants who made their way to the US at the turn of the 20th century, could join the American upper class? Their dreams and schemes seemed as unlikely to bare fruit as the sad seeds that grew the enormous beanstalk that Jack climbed into the kingdom in the sky. The Rappoports, like Jack and other folktale protagonists, seemed untroubled by shame or guilt. If one door would not open, there must be another door to try, Minnie and Phil reasoned, separately and together.

In the nearly 20 years I knew my grandparents, they did not speak a word to one another, although they did live together in what we thought of as Grandma Minnie’s house. When Phil died, all their stuff that resided there became her stuff. And when she died, her non-descript, short will left my mother $10K for the care she provided and a simple statement that everything else would be divided equally among her three heirs. I speculate that my mother initiated the will, designed to ensure that her modest bequest remained unquestioned. I also believe that because the valuable items were never appraised, no taxes were ever paid on the “stuff”… until many years later when the Rembrandt was inadvertently discovered and sold.

Unlike the Sauls, the Rappoports never hugged and rarely smiled. Moreover, I think they barely suffered from depression or self-doubt.

My friend Ted, himself and immigrant and always an A+ student in a sea of A friends, wrote saying that he had always seen the story of the story of Jack and the Beanstalk as an introduction to “adolescent phallic self-assertion” rather than an immigration narrative.” (He goes on—as I invite him to do here) to compare the Ogre to Trump.

Ted is right, of course, on all counts, but my comparison came from a different place. I realized that the Rappoports seemed immune to feelings of guilt and shame. Were they like the Greek gods in that regard? But that comparison literally reified them and made them more powerful than they were or even thought they were.

Then my friend Rosemary pointed out the characters in folktales also never entertained guilt. Here was Jack, for instance, who not only felt justified in stealing the giant’s gold, but also went back again and again for more. Moreover, like other tricksters, he fooled the giant’s kind wife who furthered his aims, and then finally, he killed the giant himself.

This reading surely doesn’t give in or sympathize with the tale as Ted’s interpretation does, but it did help me name a feeling I wanted to talk about.

This is all just to say that the same story can serve different functions for the reader. My next post will address that point.

Phil wasn't all bad, either. I guess few are.

Thanks for being readers. You keep me writing.